Caption: Far more delicate than the tug on a spider's web: If a fifth force is out there, its impact on our world must be nearly imperceptible. iStockphoto

At the turn of the 20th century, finding a new form of radiation could put a physicist’s career on the fast track. Wilhelm Röntgen changed the world by discovering X-rays in 1895. Soon thereafter, Ernest Rutherford and Paul Villard identified three different kinds of radiation, dubbed alpha, beta, and gamma rays, emitted by radioactive compounds. In 1903 French scientist René Blondlot added to the frenzy with his announcement of N-rays, a strangely democratic form of radiation emitted by wood, iron, living organisms—just about anything at all.

Some 300 scientific papers were written about N-rays. There was just one problem: They weren’t real. A skeptical physicist named Robert Wood visited Blondlot’s lab and secretly removed a key part of his apparatus; this had no effect on Blondlot’s perception of N-rays, showing that they were purely a product of the imagination.

Blondlot’s reversal of fortune served as a reminder that the world isn’t really full of countless kinds of radiation waiting patiently to be discovered. Nature is more parsimonious than that. Even as forms of radiation seemed to proliferate, theory was driving physics the other way, toward consolidation. X-rays and gamma rays were soon recognized as different forms of electromagnetic radiation, like radio waves and visible light but more energetic. Beta rays are simply fast-moving electrons, and alpha rays are fast-moving helium nuclei. Beneath the dazzling array of new phenomena lurked just a few simple ingredients...

Looking for some help with cooking your Thanksgiving feast this holiday? Here are a couple of ways that particle physics can lend a hand.

Looking for some help with cooking your Thanksgiving feast this holiday? Here are a couple of ways that particle physics can lend a hand. Heavy ion collisions allow us to recreate the density and temperature that existed at the very beginning of the universe, before the universe was 10-6 s old, in a laboratory environment. Studying the resulting hot dense matter, which we call a quark gluon plasma (QGP), allows us to both better understand the evolution of the [...]

Heavy ion collisions allow us to recreate the density and temperature that existed at the very beginning of the universe, before the universe was 10-6 s old, in a laboratory environment. Studying the resulting hot dense matter, which we call a quark gluon plasma (QGP), allows us to both better understand the evolution of the [...] Une des particules les plus recherchées en physique des particules, le boson de Higgs, semble jouer à la cachette. C’est peut-être parce qu’il n’existe tout simplement pas! Tout ce que nous physiciennes et physiciens savons c’est que quelque chose manque à la théorie actuelle. Ce pourrait être le boson de Higgs, ce qui serait la [...]

Une des particules les plus recherchées en physique des particules, le boson de Higgs, semble jouer à la cachette. C’est peut-être parce qu’il n’existe tout simplement pas! Tout ce que nous physiciennes et physiciens savons c’est que quelque chose manque à la théorie actuelle. Ce pourrait être le boson de Higgs, ce qui serait la [...] One of the most sought after particles in our field, the Higgs boson, is playing hard to catch. It might be that it does not even exist. All we physicists know is that something new is required by the theory. It might be the Higgs boson: that’d be the simplest solution, or we need to [...]

One of the most sought after particles in our field, the Higgs boson, is playing hard to catch. It might be that it does not even exist. All we physicists know is that something new is required by the theory. It might be the Higgs boson: that’d be the simplest solution, or we need to [...] Physicist Sascha Mehlhase may have missed the actual construction of the ATLAS detector at CERN, but he found another way to experience the joy of building it – a way reminiscent of his childhood and the contents of a particularly good toy box he once had. He made the detector out of Legos.

Physicist Sascha Mehlhase may have missed the actual construction of the ATLAS detector at CERN, but he found another way to experience the joy of building it – a way reminiscent of his childhood and the contents of a particularly good toy box he once had. He made the detector out of Legos. Announcement: I’ve been selected as a finalist for the 2011 Blogging Scholarship. To support this blog, please vote for me (Philip Tanedo) and encourage others to do the same! See the bottom of this post for more information. In recent posts we’ve seen how the Higgs gives a mass to matter particles and force particles. [...]

Announcement: I’ve been selected as a finalist for the 2011 Blogging Scholarship. To support this blog, please vote for me (Philip Tanedo) and encourage others to do the same! See the bottom of this post for more information. In recent posts we’ve seen how the Higgs gives a mass to matter particles and force particles. [...] This post, originally published on 11/18/11 here, was written by Kétévi Adiklè Assamagan, a staff physicist at Brookhaven National Laboratory and the ATLAS contact person for the ATLAS-CMS combined Higgs analysis. Today we witnessed a landmark LHC first: At the HCP conference in Paris, friendly rivals, the ATLAS and CMS collaborations, came together to present [...]

This post, originally published on 11/18/11 here, was written by Kétévi Adiklè Assamagan, a staff physicist at Brookhaven National Laboratory and the ATLAS contact person for the ATLAS-CMS combined Higgs analysis. Today we witnessed a landmark LHC first: At the HCP conference in Paris, friendly rivals, the ATLAS and CMS collaborations, came together to present [...] A new paper argues convincingly that Newton's constant G does not run with energy. This is a criticism of many papers that claim that such a running exists.But one moment: the strand model also makes this point. (And Schiller does not even mention it, I think.) So his model is vindicated again.

A new paper argues convincingly that Newton's constant G does not run with energy. This is a criticism of many papers that claim that such a running exists.But one moment: the strand model also makes this point. (And Schiller does not even mention it, I think.) So his model is vindicated again. At long last, here it is! From the Hadron Collider Physics conference in Paris, and as documented by the CMS and ATLAS collaborations, the plot you have all been waiting for: As we last saw, CMS and ATLAS had each set limits on the rate of production of standard-model Higgs bosons at the Lepton-Photon conference [...]

At long last, here it is! From the Hadron Collider Physics conference in Paris, and as documented by the CMS and ATLAS collaborations, the plot you have all been waiting for: As we last saw, CMS and ATLAS had each set limits on the rate of production of standard-model Higgs bosons at the Lepton-Photon conference [...] A couple of fundamental great news, well one is just a rumor, is hitting scientific community today. Higgs search At Paris Conference, Gigi Rolandi addressed his talk on combination for LHC and Tevatron. This picture has been waited for a long time since the excellent work of Phil Gibbs at his blog (see here for [...]

A couple of fundamental great news, well one is just a rumor, is hitting scientific community today. Higgs search At Paris Conference, Gigi Rolandi addressed his talk on combination for LHC and Tevatron. This picture has been waited for a long time since the excellent work of Phil Gibbs at his blog (see here for [...] The CMS and ATLAS experiments at the Large Hadron Collider have backed the Standard Model Higgs boson, if it exists, into a corner with their first combined Higgs search result.

The CMS and ATLAS experiments at the Large Hadron Collider have backed the Standard Model Higgs boson, if it exists, into a corner with their first combined Higgs search result. The OPERA experiment’s surprising superluminal neutrino result is holding fast after a new measurement designed to eliminate a possible source of systematic error from their previous tests.

The OPERA experiment’s surprising superluminal neutrino result is holding fast after a new measurement designed to eliminate a possible source of systematic error from their previous tests. This week the Large Hadron Collider began heavy ion physics, the process of colliding lead ions to learn about conditions in the primordial universe.

This week the Large Hadron Collider began heavy ion physics, the process of colliding lead ions to learn about conditions in the primordial universe.  Fermilab’s Tevatron program has shut down, but the laboratory’s other programs are going strong. Learn more about Fermilab’s future programs through the monthly Physics for Everyone lectures beginning again on Wednesday, Nov. 16.

Fermilab’s Tevatron program has shut down, but the laboratory’s other programs are going strong. Learn more about Fermilab’s future programs through the monthly Physics for Everyone lectures beginning again on Wednesday, Nov. 16. TweetWe have shown throughout the Imagineer’s Chronicles and its companion book "The Reality of the Fourth spatial dimension" there would be many theoretical advantages to assuming space is composed of four *spatial* dimensions instead of four dimensional space-time. One of them is that it would allow for a logical explanation of the superposition principal associated [...]

TweetWe have shown throughout the Imagineer’s Chronicles and its companion book "The Reality of the Fourth spatial dimension" there would be many theoretical advantages to assuming space is composed of four *spatial* dimensions instead of four dimensional space-time. One of them is that it would allow for a logical explanation of the superposition principal associated [...] Scientists from the LHCb collaboration at CERN recently saw curious possible evidence of this asymmetry: The difference between the decay rates of certain particles in their detector, D and anti-D charm mesons, was higher than expected.

Scientists from the LHCb collaboration at CERN recently saw curious possible evidence of this asymmetry: The difference between the decay rates of certain particles in their detector, D and anti-D charm mesons, was higher than expected. The latest underground dweller in the MINOS tunnel is SciBath, a neutron and neutrino detector designed and built by an Indiana University team. Scientists are using the detector cube, which is about the size of a mini fridge, to track neutrons and neutrinos more effectively and economically.

The latest underground dweller in the MINOS tunnel is SciBath, a neutron and neutrino detector designed and built by an Indiana University team. Scientists are using the detector cube, which is about the size of a mini fridge, to track neutrons and neutrinos more effectively and economically. I had the chance to meet Federico in a series of conferences organized by Rodolfo Bonifacio of University of Milan at Gargnano on Garda Lake. The last time I met him was on September 2003 at this conference. Federico was an associate professor at University of Milan, an expert in quantum optics, and it was [...]

I had the chance to meet Federico in a series of conferences organized by Rodolfo Bonifacio of University of Milan at Gargnano on Garda Lake. The last time I met him was on September 2003 at this conference. Federico was an associate professor at University of Milan, an expert in quantum optics, and it was [...] As my readers know, a recurring question in this blog is the solution to the Millenium Problem on Yang-Mills theory. So far, we have heard no fuzz about this matter and the page at the Clay Institute is no more updated since 2004. But in these years, activity on this problem has been significant and [...]

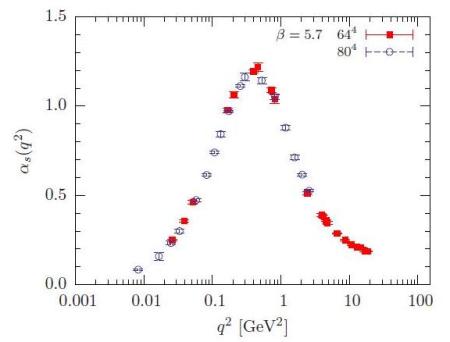

As my readers know, a recurring question in this blog is the solution to the Millenium Problem on Yang-Mills theory. So far, we have heard no fuzz about this matter and the page at the Clay Institute is no more updated since 2004. But in these years, activity on this problem has been significant and [...]